Micheal Rainvelle Jr / Mill City TImes: Five hundred million years ago a giant, shallow, tropical sea covered the vast majority of what later became North America, including the central and eastern portions of Minnesota. This resulted in a very thick layer of St. Peter Sandstone developing with a thinner layer of Platteville Limestone forming on top of it. These layers made it possible for St. Anthony Falls to erode upstream to where it sits today along the downtown riverfront. However, these geological layers are also the perfect recipe for caves and tunnels to naturally form. Once European settlers established the towns of St. Paul, St. Anthony, and Minneapolis, they too took advantage of the soft sandstone and dug out cave systems for various uses. It is because of this that some say the subterranean world of the Twin Cities is comparable, if not grander, than the catacombs of Paris. These next three stories are just a small portion of what lies beneath our feet.

Chute’s Cave

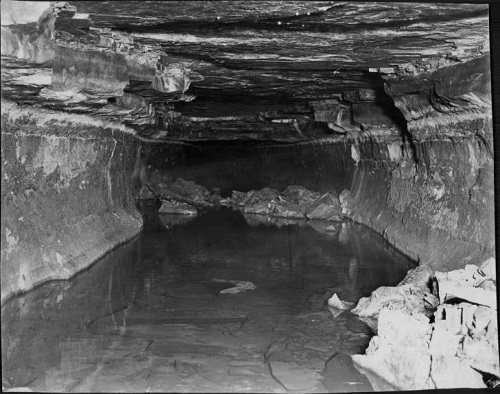

Photo of a collapsed section of Chute’s Cave taken in 2000 by urban explorers, Action Squad.It didn’t take a well-learned person to figure out that the exposed sandstone along the bluffs of the Mississippi can be easily manipulated. Once the riverbanks were filled with lumber and flour mills, entrepreneurs began exploring the possibility of using tunnels to power their mills. One of the first to try this out was Samuel H. Chute, namesake of Chute Square, the location of the oldest house in the city, and an agent for the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company. He wanted to dig a tunnel underneath Main Street of over 1,100 feet. Workers digging out Chute’s Tunnel were stopped a few hundred feet in from the shoreline when they broke through into a large cavern.

Photo of the formation “Chute’s Medusa” taken in 2001 by Action Squad. It measures roughly six feet wide.

Originally, Chute’s Cave was 200 feet long and 100 feet wide, and in the middle was a large geological formation, likely a stalagmite, that was dubbed the Tower of St. Anthony. In 1866, the St. Paul Daily Press reported that some explorers lifted up a slab of malachite in the cave, and underneath was a spiral staircase. After descending 123 steps, it opened up into Chute’s Cave, where they saw human-sized stalagmites rising up, and diamond-like stalactites glistening on the ceiling. The columnist then ended their report by saying that Chute’s Cave “is supposed to be the place where good St. Antonians go when they die.” It must’ve been a slow news day.

Woman entering Chute’s Cave by boat, photo courtesy of Dr. Greg Brick

The Eastman Tunnel Collapse of 1869

A resort was opened on the bluffs near the cave’s entrance and even offered torchlight boat tours of the stunning cave system. Unfortunately, the beauty of the cave changed on December 23rd, 1880 when a portion of the cave collapsed, taking some of Main Street with it. Once the area was stabilized and the street was back up and running, the cave was deemed unsafe and the resort was abandoned. Years later in the 1960s, the city pondered the idea of turning the cave into a fallout shelter, but that idea was abandoned.

Scan from loan for copy negative on Epson Expression 10000XL.

Before Main Street sank into Chute’s Cave, businessmen William Eastman and John Merriam purchased the majority of Nicollet Island with the intent to mill along the island’s shores. The two argued that the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company controlled all of the water power on the east side of the falls, so they sued the company and won. The two parties agreed that Eastman and Merriam could dig a tunnel underneath the falls from Hennepin Island to Nicollet in order to take advantage of the falls fifty-foot drop to create 200 horsepower to operate their mills.

Digging started in September of 1868 and workers slowly dug their six-by-six-foot tunnel 2,500 feet to Nicollet Island. By early October 1869, the crew made it 2,000 feet in and reached the southern tip of Nicollet Island. They were almost there. Towards the end of the workday on October 4th, some workers noticed a very small leak in the tunnel. The next day when they arrived at the site, they discovered that that the river turned the small leak into a giant hole, and the river quickly carved out a seventeen-foot deep hole ninety feet wide!

Over 100 men from St. Anthony volunteered to help save St. Anthony Falls, and more important to them, the power it was capable of producing. They started throwing rocks and logs into the giant hole, but they were tossed around and swept away like toothpicks. The power of the mighty Mississippi was just too much. Eventually, the Minneapolis Fire Department came to the rescue, and with the help of even more volunteers, they constructed three cofferdams to stabilize the falls. Wood will obviously erode over time, so the dams had to be replaced every four years or so until the 1950s when the Army Corps of Engineers installed the concrete apron that makes up St. Anthony Falls today.

1940 photo of the remnants of the Eastman Tunnel

Nicollet Island’s Many Secrets

Remnants of tunnels from the Eastman tunnel collapse are still located throughout the southern tip of Nicollet Island. These are known as the Neapolitan Caves because of iron-red swirls mixed into the white and green sandstone walls. Further up the island is a tunnel dubbed the “bloody snake passage” by local explorer, historian, and author of the book Subterranean Twin Cities, Dr. Greg Brick. He gave this tunnel, which dead ends at the foundation of DeLaSalle High School, its name because of scarlet-red flowstones along the walls that resembled dripping blood.

The two most prominent caves can be found around the northern tip of the island. First, accessible from an old utility tunnel that forms a loop around the island, Satan’s Cave is aptly named because of bas-reliefs carved in the sandstone of demonic figures and a small alter with a candelabra on top. The carvings were created in such a way that when lit candles are placed in the mouths of the carvings, light glows out of their flaring nostrils. These carvings and the alter are fairly recent, appearing no earlier than the mid-1970s when a Minneapolis Star reporter explored the caves on the island and did not note anything demonic. Satan’s Cave used to have a more important use, however. When John Orth became the first brewer in Hennepin County in 1850, he would use this cool cave to keep his lager chilled. Eventually, Orth would go on to establish the Minneapolis Brewing Company. Once Orth left the cave, it was used the grow mushrooms through the 1920s.

Underground entrance to Satan’s Cave

Carvings and candles inside Satan’s Cave

The last notable cave on Nicollet Island is Santa’s Cave, a transposition of Satan’s Cave, done by Dr. Brick. Prior to this name, it was known as Cave X, for its cross-like shape. While more impressive than Satan’s Cave, Santa’s Cave is hard to access, so most urban explorers leave it for the two species of bats that hibernate there in the winter months.

These caves are still around today, but don’t be fooled, they are still dangerous. That early explorer who found a spiral staircase down into Chute’s Cave said the stairs were made out of polished marble with brass bannisters. Earthly gasses, like methane, can get trapped in these caves. Perhaps this explorer’s tall tale was influenced by trapped gasses and a lot of time on their hands? A French explorer claimed to have studied hieroglyphs in a vault on Nicollet Island, and he concluded that beyond the vault was a room full of treasures where an extinct race of very smart, flying humans kept their knowledge. Maybe the gasses got to him and he saw bats flying by his head? More recently, in the late 1900s, a resident of Nicollet Island was exploring one of the many tunnels and passed out from inhaling too much methane. Luckily, he was with a friend who pulled him out and he came to once they were topside. Caves are pretty neat, but they are blocked off for a reason. Hopefully one day we can safely explore Minneapolis’ subterranean world.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

A 6th generation Minneapolitan, Michael Rainville Jr. received his B.A. in History from the University of St. Thomas, and is currently enrolled in their M.A. in Art History and Certificate in Museum Studies programs. Michael is also a historic interpreter and guide at Historic Fort Snelling at Bdote and a lead guide at Mobile Entertainment LLC, giving Segway tours of the Minneapolis riverfront for 7+ years.