’70s Homeware Was Loud, Eclectic & Optimistic. No Wonder It’s Back!

Photo by Justine de Villeneuve/Getty Images

–

British fashion model Twiggy wearing a black dress with a black hat and pink suede high heels in Biba’s Kensington store, 1971

–

Refinery29: If you’ve never seen it before, you should look up pictures of London’s “Big Biba” shop. The seven-story department store opened in Kensington in 1973 following the explosion in popularity of Barbara Hulanicki’s fashion brand. While Biba is often associated with the 1960s (the first store opened in ’64), the interior of Big Biba was, in many ways, quintessentially ’70s. There were loud prints on the home floor, curved edges, soft geometric shapes, and a special commitment to earthy browns and oranges. It was a mishmash of art deco-inspired interiors reminiscent of the golden age of Hollywood, animal prints and beaded fringe, with an eclectic mix of trinkets and low lighting that really brought it all together. It was made to feel intimate, almost seductive — an explicit rejection of the stark lighting and synthetic color palettes of the ’60s.

–

Until the last few years, ’70s home design remained a largely reviled aesthetic. The rise of Britpop in the ’90s created pockets of ’70s nostalgia and a few trends from the decade have taken on a life of their own (hi, houseplants) but for the most part, ’70s home styling, particularly the swirling wallpaper and autumnal palette, was understood to be an ugly mistake. Sneering books have been written about it, such as Interior Desecrations: Hideous Homes From The Horrible 70s. Online, there are forums full of people asking, “Why were such awful colors popular in the 1970s?“

–

PHOTO BY PHOTO MEDIA/CLASSICSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

–

Archival 1970s image of a mother and a son in their orange and brown kitchen.

Yet ’70s interiors have come back around. Bit by bit, small trends like macramé, rattan, and houseplants have been leaking into modern home decor and the decade is now being embraced with open arms. But why the ’70s? And why now?

–

–

When it came to design, the ’70s was an era of play, eclecticism, and optimism. According to Dr. David Heathcote, senior lecturer in graphic design and illustration at the Liverpool School of Art and Design, the period was defined by the transition from modernism into something much more free-form and forward-thinking. “There was no heterogeneous style or styles — it was a free-for-all. Even where it referenced earlier, historic styles, which it began to do, it was in a very obvious and playful way, a kind of non-nostalgic timelessness.”

–

For homemakers and homeware consumers, the ’70s marked a shift towards the idea that your home could be playful. “I think there was a lot more broad playing with aesthetic ideas which people accepted,” says Dr. Heathcote. “They got used to the idea they could have things in many, many different styles. It was a massively eclectic period.”

–

What Dr. Heathcote calls the “dressing-up-box culture” of all the subcultures in the ’60s meant that there were many people coming of age in the ’70s who took their subcultural approach from their fashion to their interior design. “You’ve been a rebellious teenager, you leave home, you find a flat you want to stay in, and then you redesign it — all the effort that you put into your dressing is suddenly put into your housing.”

–

–

This desire to experiment can be linked to a broader sense of liberalism and curiosity about the world which emerged in the ’70s. Much of the craft revival (particularly with materials like rattan and skills like macramé) can be traced back to what Dr. Heathcote calls an “increasing interest in, for want of a better word, ‘ethnic’ cultures.” There was an idea that a liberal outlook involved not just an acceptance but an enjoyment of other people’s cultures, and by showcasing these influences in your home, you were parading your “embracing the world type approach.” It’s the home design mentality equivalent of popular ’70s backpacking route, the hippie trail — seen just recently in BBC One’s The Serpent.

–

The problem with our perception of the ’70s as dark and dingy is actually not so much an issue of color as of lighting and fabrics. This was the era of dimmer switches, plush materials like velvet and, frankly, explicitly seductive design. The boudoir feel of places like Biba was inviting after the stark, jolly brightness of the ’60s. To design in a way that was seductive, by ’70s standards, was precisely the point. “There was a heavily eroticised angle to a lot of ’70s design,” says Dr. Heathcote. “It’s as if the permissive society that evolved in the late ’50s and through the ’60s turned itself into designs because there was an awful lot of dalliance with dungeon-like interiors at its most extreme.”

–

Ultimately, despite economic hardships at home, the ’70s held a sense of optimism about the future as travel and technology grew. This was reflected in home design: things may be bad now but they could be better. Perhaps our renewed interest in ’70s design in 2021 speaks to our wish to return to this sense of optimism and curiosity and even (whisper it) joy. But unlike the forward-looking ’70s, we’re now looking back, seeking comfort in a decade that seems a world away.

–

Estelle Bilson, the woman behind the much-loved Instagram account @70sHouseManchester, has been collecting ’70s homeware in some form since she was a small child, in part thanks to her father’s career as an antiques dealer. While there is something about the ’70s that she inherently loves, there is also a clear link back to her childhood.

–

“My parents think it’s really funny because I’m literally buying back the stuff they had in the ’70s. The sunburst rug I have in my dining room is so similar to the one my parents had in the ’60s and ’70s when they lived in London. That style rug was in my bedroom ’til I was about 13 and then it mysteriously got thrown away. I was really upset about that. It took me 15 years to find one to replace it. I had that, and I loved that as a kid, it anchored me in my childhood and really happy times so finding it again was almost like a security blanket. There’s probably some Freudian reason behind why I collect.”

–

This sense of nostalgia continues with the story that secondhand pieces carry with them, says Natasha Landers, a diversity consultant in Walthamstow who has a love of interior design. “I’m a child of the ’70s and the designs are very nostalgic for me as they remind me of pieces that we had in my home growing up. I am really interested in the fact that each piece will have a story behind [it]. Last year I bought a coffee table from a house clearance and the woman who sold it to me, it was her deceased parent’s house. When I was putting it into the car, she said she remembered playing cards on the table as a child.”

–

There is a wealth of reasons why people are drawn to the ’70s in the 21st century. For some, it’s just a gut pull towards the shapes, textures, and colors of the decade. “If you look at the Evelyn Redgrave piece of fabric I’ve got on my wall,” Estelle says, “with the big swooping colors and the oranges and browns… There’s obviously something in me that I look at it and go ‘Wow.’ I’m sure other people go ‘Eurgh.'”

–

–

For others, it is a more explicit rejection of “modern aesthetics.” Isabella Bondo, a student living in Denmark, finds the dominant Scandinavian style “impersonal, clean, and boring.” “In Denmark, it feels like everyone else has the exact same interior style. If that’s what counts as modern design, I’m really not into it. The most important thing for me when it comes to interior design is personality and personal style, and I don’t feel that with modern design aesthetics.”

It is also a rejection of consumerism. Yvonne Chappell, who works in education and lives in Scotland, was initially drawn into ’70s design when she and her fiancé moved into their house, which was built in 1973. “I was immediately fascinated by retro interior design and particularly the colors seen throughout ’70s homes of the time. Being 24, I’ve grown up in a sort of throwaway society where styles change so quickly and things aren’t often built to last (I realized this after buying SO much flat-pack that kept breaking). Seventies furniture can be found in excellent condition to this day; the quality of furniture clearly stands the test of time. I like the idea of loving something that was designed well and designed half a century ago.”

–

–

We can even thank (?) the pandemic for accelerating some facets of ’70s design. With access to outdoor spaces severely limited by a series of lockdowns, the desire to bring nature inside both literally and figuratively has soared. The craze for houseplants and other forms of gardening shows no sign of abating. Equally, a pull towards warmer, earthier tones in homeware and interiors can be linked to a growing movement towards design that brings nature into our homes, says registered interior designer Nicola Holden. “Another growing movement in interior design is that of biophilic design, or bringing a connection to nature into our homes. A lot of the ’70s trends incorporate this, such as wood paneling, shag pile carpets, fringing, the use of natural materials and texture (exposed bricks and textured walls), and curved shapes.”

–

This ties in intimately with the trend towards sustainability, whether it’s earthenware ceramics made by independent artists to house our cheese plants, taking up hobbies to DIY our own crochet blanket or macramé wall hanging, or using more sustainable materials like rattan and cork. By choosing to support small businesses or buy products with a lower carbon footprint, you are inadvertently embracing a ’70s approach to design.

–

–

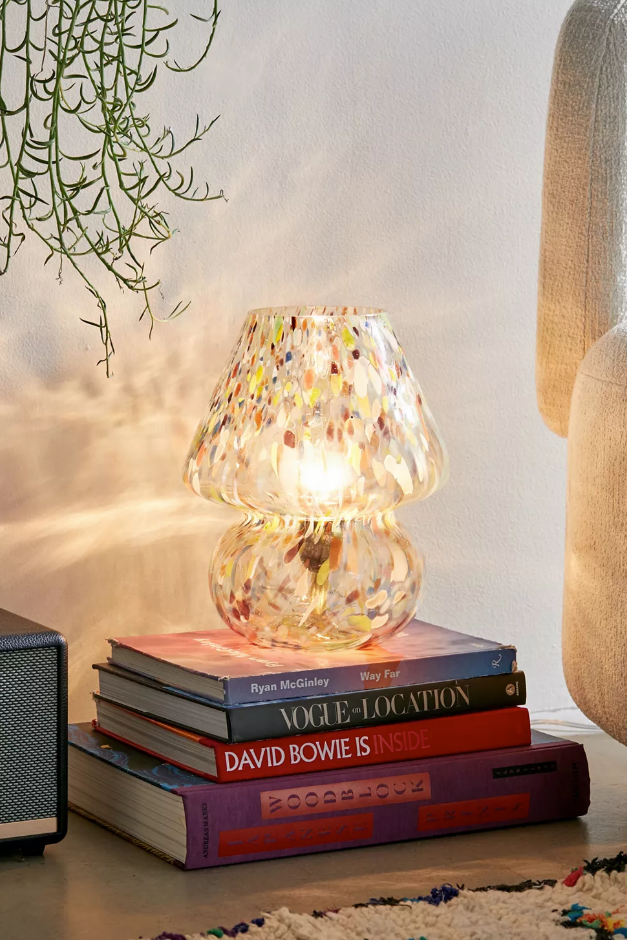

Even our pull towards statement lamps is ’70s-esque. Our current desire to create a sense of coziness as well as accommodating home offices has inadvertently led to a return to the low lighting of the ’70s. And the most popular lamp right now, the mushroom lamp, is a direct design import from that era.

–

The most divisive part of ’70s design is unequivocally the color palette. But after years of minimalism, Scandi chic, and the dominance of cream, grey, and beige, what once seemed gaudy now has a kind of charm. “The ’70s was a time of lurid patterned wallpapers and brightly colored upholstered furniture,” says Nicola. “Today we are definitely moving away from the beige/grey era and towards more color, as people are subconsciously realizing the energy and positivity that color gives us, which has been scientifically proven in the field of color psychology.”

–

Still, brown needs far more rehabilitation than the oranges, yellows, and avocado greens of the period.

–

“People still have a deep hatred for brown,” says Estelle. “It is a really polarising color. But actually, it’s a really good neutral to start from and it’s a really versatile, warm color.” When Estelle found the right shade for her dining room she was delighted to prove to everyone who told her not to paint it brown that, actually, it can look good.

–

–

If you want to take a step into the world of ’70s interiors, you don’t have to go all-in like Estelle, Isabella, and Yvonne. Try a softly-softly approach, choosing key ’70s pieces to style as part of a wider eclectic home design. As Camille Montalbo, an American-based thrifting aficionado, told Refinery29, “The way the furniture mixes together is pretty effortless.” Key pieces of furniture like chairs and tables end up being statements, which mesh well with other eras thanks to the simple lines of the design. Camille’s Jerry Johnson Sling Chair remains one of her favorite finds for that reason.

–

Plus, finding secondhand goods from the era is made easier by the huge proliferation of pieces available. The volume of designs being produced and a sharp increase in consumption mean that there was a lot of design about. And if it’s lasted this long, be assured it will last well into the future.

–

Beyond furniture, there is a wealth of ’70s-style home decor — both vintage and modern — to add warmth to a room or a statement to a corner, from lamps to sunburst mirrors to velvet throw pillows. If you’re feeling particularly inspired, why not branch into patterned wallpaper — Estelle has recently launched a homeware business of made-to-order wallpapers and fabrics.

–

The most important thing is to use your instincts and buy what you love. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a ”90s does ’70s’ lamp or something a little bit silly,” says Estelle. “If you absolutely love it, you will have it in your home and you will never tire of it.” And if you’re still put off by the perceived dinginess of the ’70s, just make sure your space is well lit.

–

At Refinery29, we’re here to help you navigate this overwhelming world of stuff. All of our market picks are independently selected and curated by the editorial team, but if you buy something we link to on our site, Refinery29 may earn commission.