Lockdown has challenged regressive sexist attitudes towards the craft, and the results are impressive

Before the local government could stop him, Simanjuntak raided thrift shops for fusty fabrics, damaged clothes and any rag that might prove useful. Three months later, after a lot of trial and error and YouTube tutorials, he uploaded his first big project to the 260k-strong Reddit community /r/sewing: A Dickies-inspired work jacket, upcycled from a blanket and some floral curtains he found at Goodwill. It immediately shot to the top of a subreddit almost entirely dominated by dresses. “Thank you everyone for the nice comments,” he wrote at the top of the post, which gained seven thousand upvotes. “I’m smiling a lot rn!”

It should come as no great surprise that /r/sewing has grown in popularity. As stringent lockdown measures loomed, the world got busy keeping busy. Google searches for ‘sewing machines’ jumped by 400 per cent in the US, and John Lewis reported that sales of them had risen by 127 per cent over April. What might come as a surprise, however, is the amount of men who began posting their own creations – from face masks to full outfits – on the forum, a real rarity before the pandemic hit. “I see a lot of new seamsters like me popping up in the subreddit every day,” Simanjuntak tells me. “The first time you put your own work on your body feels like magic – it’s wild addicting.”

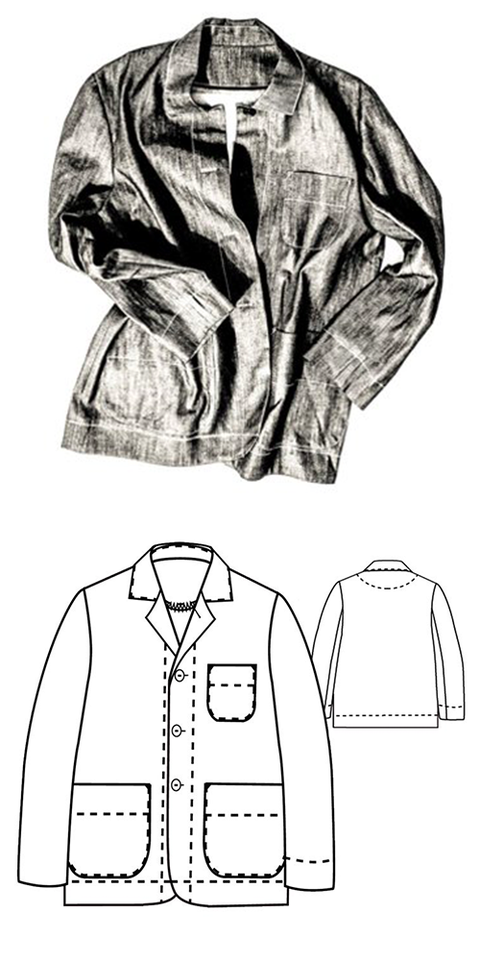

According to Merchant & Mills, a former warehouse-turned-sewing emporium in Rye, East Sussex, more men than ever are taking to the craft. The British draper received a month’s worth of orders each day at the start of lockdown, but it was their template for a men’s workwear silhouette that reigned supreme. “The Foreman Jacket shot through the roof. It was the best-selling pattern by miles,” says Carolyn Denham, who co-founded the company ten years ago. Even before lockdown, she noticed that men were finally beginning to see the value in producing their own clothes with long-lasting materials. “Sewing doesn’t have to be this mumsy, cutesy thing with pink scissors,” she tells me. “Men relate to it being a ‘quality’ thing. I think they hook straight into that.”

Why do so few men sew? In truth, the history of the sewing machine is bound in misogyny – a depressing totem of how emancipation and oppression can intertwine. The breakthrough tool was hailed as a huge time-saver upon its invention in the mid-19th century, but the major beneficiaries turned out to be factory owners. Foot-powered sewing machines allowed crowded, poorly ventilated sweatshops, staffed almost entirely by women, to mass-produce clothes for the first time. For several months of the year, it was common for poverty-stricken British seamstresses to work twenty-hour days sewing à la mode dresses for wealthy women. Needless to say, they were often expected to craft and fix clothes for their own families, too. The industry’s pitiful wages were compounded by the fact that men, who controlled the bespoke tailoring trade, blocked women from joining their trade unions.

Of course, that problem has never gone away – it’s simply been outsourced to poorer countries and hidden from plain sight. Less gendered, sure, but just as unequal. This year, The Guardian discovered that a factory in Leicester that provided clothes to Boohoo, the biggest fast fashion company in the world, was secretly paying labourers £3.50 an hour to work through lockdown with no social distancing measures. For Redditor Mehedi Sarri, the scourge of modern slavery was one of the main reasons he picked up a needle in the first place. “When you start sewing, spending six to eight hours on a garment, you realise the value of your clothes. Then you start doing the maths and it doesn’t add up. How is it possible to sell clothes so cheap?” he says. “I understood that the sewing process is industrialised, but it is at that moment that you really realise the exploitation of others and our planet.”

Sewing with quality materials can be expensive – more expensive than buying clothes from a high street shop, anyway – and the equipment costs can be prohibitive too. But the ethical upcycling movement, spearheaded by designers like Emily Adams Bode, Sam Nowell and Greg Lauren (nephew of Ralph), is encouraging people to make the most of what we already, collectively, have. Jonathan Simanjuntak’s aforementioned floral jacket, a one-of-a-kind item, cost £15 to make. Ishmael Jasmin, a 20-year-old Redditor from Los Angeles, has even started selling his own streetwear pieces crafted with woven blanket materials, including a pair of Space Jam-themed shorts. “Sewing has been very beneficial to my mental health,” he tells me. “Don’t get me wrong, some projects can be draining and annoying. But when I’m creating something, I don’t have to really worry about any outside noise. Just me and my machine is a perfect combo.”

Esquire Style Director Charlie Teasdale has always tried to support the callus-thumbed crafters of the fashion industry as much as possible, but he believes that men could stand to learn some DIY skills. “I think clothes-making is one of those lost arts that our ancestors would be saddened to learn the death of. (Sorry, ancestors. We have Arket now.) It’s the kind of thing we should probably all have a basic knowledge of,” he says. “Not so much in terms of making clothes, but it would be better for the world if we all had a grasp of how to fix things.”

We can’t mend all of society’s problems with a needle and thread, but we can do our bit. “Learning how to create, alter, and fix clothes is pretty crucial, but I don’t expect everyone to pick it up,” says Simanjuntak, who has been uploading more pictures of his charity shop creations despite the easing of lockdown restrictions. “This is definitely a time for people to be more in control of the quality and production of the goods they consume. I’m still going to be sewing a lot when this is all over.”